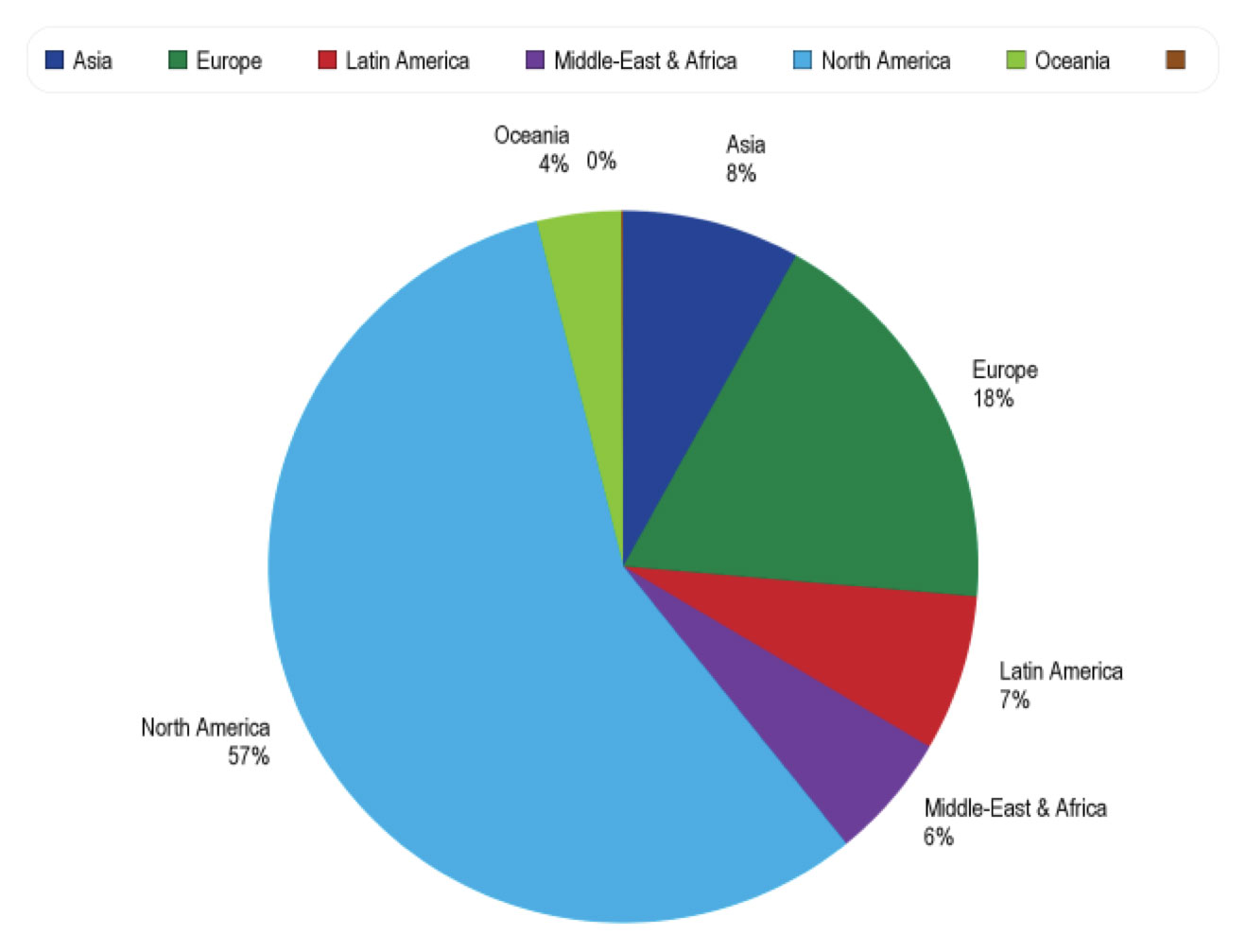

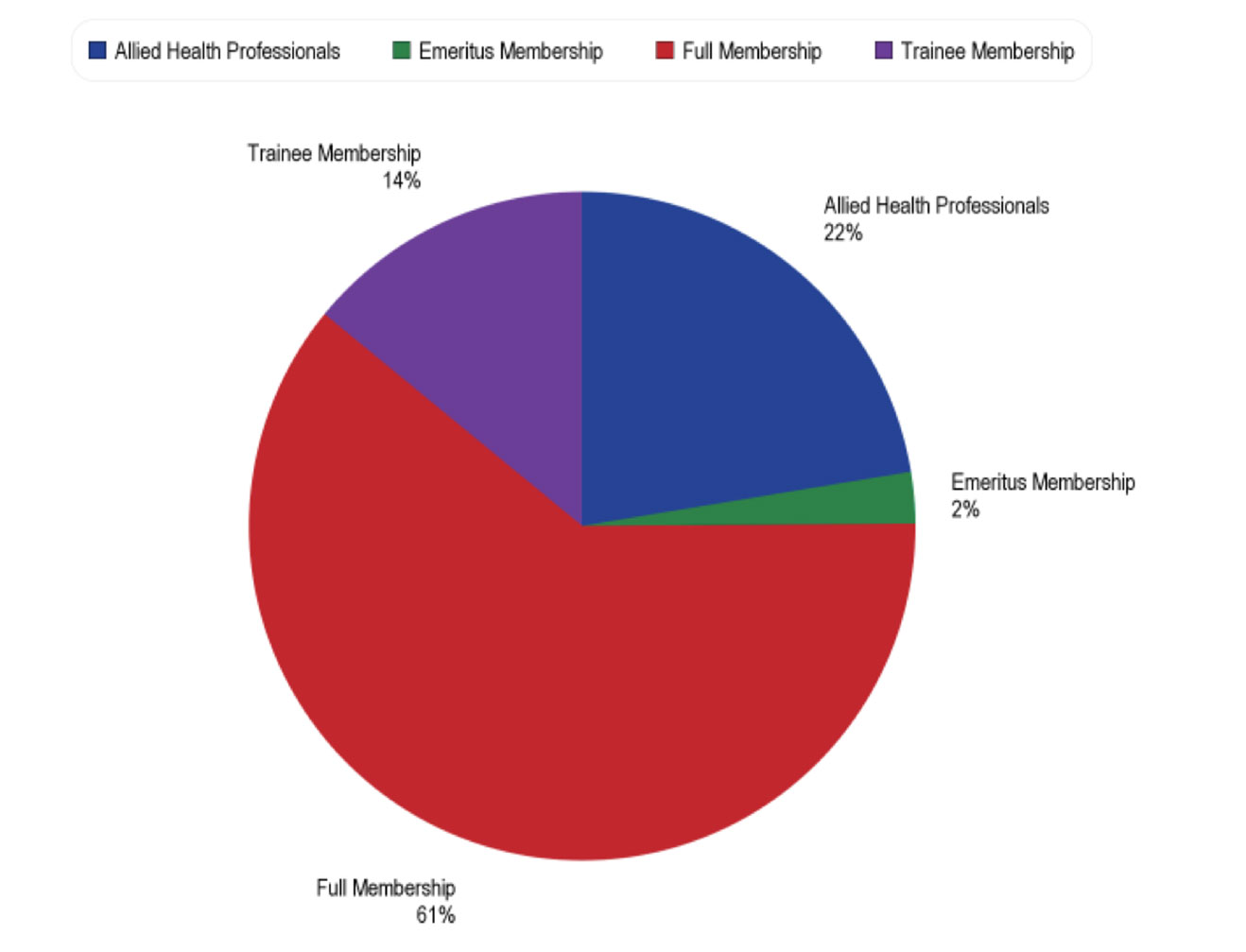

The 12th Congress of the International Pediatric Transplant Association (IPTA) event in Austin, Texas, had over 400 attendees from 40 countries. The attendees included a diverse mix of pediatric transplant professionals from several specialties including pediatricians, surgeons, scientists, nurses, organ procurement personnel, advance transplant providers, pharmacists, administrators, fellows, residents, and students. The 4-day event featured nearly 200 abstracts, 90 oral presentations, 24 mini oral presentations, and more than 80 poster presentations. All of these presentations encouraged vibrant discussions and supported the exchange of new clinical and basic science information regarding clinical care management, basic science research, socioeconomic, and ethical and organ donation issues relevant to pediatric transplantation. We briefly describe here the highest scored presented abstracts at IPTA 2023 in clinical science.

Clinical Science

1.1 Liver Transplantation

Liver transplantation had a variety of topics that included organ allocation of pediatric livers for pediatric patients, normothermic perfusion, center volumes, and outcomes of pediatric liver transplantation for specific indications. A few papers were presented on allocation of pediatric livers. The group from NYU reported on the effect of acuity circle liver allocation policy on pediatric whole liver transplantation in high versus low volume centers and they noted that the median MELD/PELD decreased at both high volume and low volume centers with an increase in donor age.1 The second paper that was also well attended with robust discussion was presented by the Stanford group who examined the outcomes of pediatric liver transplant at high volume (>5 transplants per year) center versus low volume centers.2 Patients who travelled >100 miles to receive an out-of-state liver transplant at a high volume center had a better graft survival than patients who received a liver transplant at a local low volume center. There was no difference between the groups with respect to waitlist mortality and overall patient survival.2 The consensus was that more collaboration is required between transplant centers to exchange best practices to continue to improve access to care and outcomes for pediatric liver transplant recipients. New Zealand introduced a intention-to-split deceased organ livers in 2016, whereby all suitable organs from donors of 40 years and younger are split between a pediatric and adult recipient.3 The study presented from the University of Auckland group showed that the waitlist mortality had a downward trend (9.1 to 4.4%) and that the waitlist time was reduced for pediatric patients.3 The Dallas Children’s group reviewed 13 pediatric liver donors who had Normothermic perfusion in USA.4 The donors who received Normothermic perfusion were more likely to be DCD and have higher BMI. However, all the livers were transplanted into adult recipients and had excellent outcomes with no incidence of ischemic cholangiopathy in the DCD subgroup.4

Liver transplantation for pediatric patients with progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) was reviewed by the Emory group and they noted that, unlike previous reports of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) occurring only in PIFC2, histologically proven HCC occurred in PFIC3 patients and recommended all patients with PFIC waiting for a liver transplant should be screened for HCC.5 The prevalence of portal vein obstruction from the Portal vein obstruction revascularization therapy after liver transplantation (PORTAL) registry from a 15 transplant centers collaborative was presented by Alfares et al.6 They noted that the overall prevalence of portal vein obstruction was 6.4% among all the patients and the highest prevalence (20%) was seen among biliary atresia recipients who were transplanted younger than one year of age using a living donor graft, and suggested that future studies should focus on prevention in this high-risk group.6 Bone Disorders are frequent in children undergoing liver transplantation. Astolfi et. al., presented a review of 105 children from Switzerland and they noted that 22 (21%) patients experienced pathological fractures.7 Patients with cholestatic liver disease and delay in bone age were at higher risk and they noted that nutritional intervention before liver transplantation cannot completely counteract the effect of chronic hepatic osteodystrophy due to liver disease and chronic cholestasis causing malabsorption.7 Pediatric living donor liver transplant patients sometimes develop graft fibrosis. Ueno et. al., presented 12 patients, where everolimus was initiated after a protocol biopsy showed graft fibrosis (METAVIR score >1) and they noted that graft fibrosis improved in 9 of the 12 patients at a median period of 33 months.8 Mouth ulcers were the significant side effects of everolimus resulting in discontinuation of the drug in one patient.8 Early extubation after liver transplant surgery has been demonstrated in pilot studies. Maudarbaccus et. al. presented 23/192 children over a 7-year period who were extubated in the operating room and none of them required reintubation in ICU.9 Preoperative and intra operative predictors of early extubation included older age, shorter length of surgery, smaller volume of PRBC and FFP transfused, and utilization of regional anesthesia. The early extubation group demonstrated a decreased ICU and hospital length of stay.9

1.2 Kidney Transplantation

The kidney transplantation had the highest number of abstracts (59) presented. There was a broad array of clinically interesting topics. Topics ranged from best practices for assessment for transplantation, use of cell free DNA, anti-body mediated rejection, and treatment of recurrent disease.

Adetunji et. al., from Cape Town, South Africa, reported on the use of Pediatric Feasibility Assessment for transplant, an objective and transparent system to assess the eligibility for transplantation to ensure consistency and equity in patient selection and to reduce moral distress among clinicians.10 Children who were not listed for transplant scored very low in social support adherence and caregiver concerns. Of note, the children who were not listed for transplant 46.7% (14/30) died within a year. This paper underscores the urgent need to implement psychosocial support to address remediable factors such as adherence, to address socio-economic barriers such as poverty, medical insurance, and to provide more comprehensive support for children awaiting renal transplantation in South Africa.10

Incidence, risk factors, treatment strategies, and outcome of antibody mediated rejection in the pediatric kidney transplant from the Cooperative European Pediatric Renal Transplant Initiative (CERTAIN) was presented by Fichtner et. al.,11 Data from 19 centers with 331 patients showed that the cumulative incidence of acute ABMR up to five years post-transplant was 10.8% and that of chronic ABMR was 5.9%. The risk factors for development of ABMR were the number of HLA-mismatches, evidence of de novo HLA-DSA, and T-cell mediated rejection.11 ABMR was a major risk factor for premature graft loss.11The group suggested standardization of treatment of ABMR and the need to develop novel drugs for more effective therapy of ABMR.

There were a few papers presented on the use of donor derived cell-free DNA. George et. al., used a composite risk factor of high donor cell-free DNA (>0.5%) combined with tacrolimus level variability that helped identify patients at increased risk for poor graft outcomes in the early post-transplant period.12

Pollack et. al., presented the use of Rituximab for PTLD prophylaxis in pediatric renal transplant patients with EBV viremia, which increased despite immunosuppression reduction. Rituximab was effective for EBV clearance and well tolerated.13

Kadakia et. al., presented the use of Belatacept based immunosuppression for (n=18) patients, where the primary indication conversion was rejection and/or noncompliance or calcineurin toxicity.14 Median time to conversion was 37 months, 94% (17/18) of the patients were compliant with monthly infusions and had fewer rejections after conversion, and GFR was preserved in 72% (13/18) of the patients and the authors report that Belatacept is an effective option for pediatric kidney transplant patient with nonadherence.14

1.3 Heart and Lung Transplantation

Pediatric heart transplant has been performed for childhood cancer patients with end stage heart failure and most centers required two years wait time after chemotherapy completion. Gambetta et. al., presented their series of five patients who received heart transplants less than two years prior to chemotherapy completion; median time to completion of chemotherapy was six months in the study.15 Cancer diagnosis included acute lymphoblastic leukemia and osteosarcoma. All patients are alive at a median follow up of 15 years.15 The authors suggest that select patients may do well with less than the traditional two years wait time. Adolescent thoracic transplant recipients are at increased risk of psychological distress and Liang et. al., presented an iPeer2Peer Program that encouraged confidence and disease self-management in 14 thoracic organ transplant recipients.16 Delvia et. al., evaluated functional performance in 16 children after lung transplant and they noted significant limitations in physical fitness in the pediatric lung transplant recipients even at one year post transplant and emphasized the need for rehabilitation with focus on strength and endurance training to optimize recovery from lung transplantation to improve long term health in this population.17